Dear friends,

For years, I’ve kept photographs of interesting road signs, instruction signs, graffiti or random words spray-painted on the walls. Once, many years ago, I spent an hour on the phone walking up and down a residential street in West Belfast. Someone had written “I hate this street” on the wall. I thought of how long they had lived on that street to have such passionate feelings about it; all the ways their life would be in conversation with the bricks and road long after they’d left it.

A signpost is a small language act. “This way” it says, or, depending on where you want to go, it communicates “You should turn back” or “You’ve gone too far.” A sign can communicate authority, or an overstretch of authority. It can say something about time as well (“No parking here during rush hour”) or a sense of foreboding (“Crash ahead”).

These instances of public language always interest me, and while I forget most of them, there are always some I carry.

A few years ago, I was in the Botanic Gardens in Sydney, Australia, and took complete delight in a sign that said “Please walk on the grass. We also invite you to smell the roses, hug the trees, talk to the birds, and picnic on the lawns.” It was hard not to smile the first time I read the language. I took a photo (which I’ve tried to find, but can’t).

Language is power; sometimes — but not always — necessarily so.

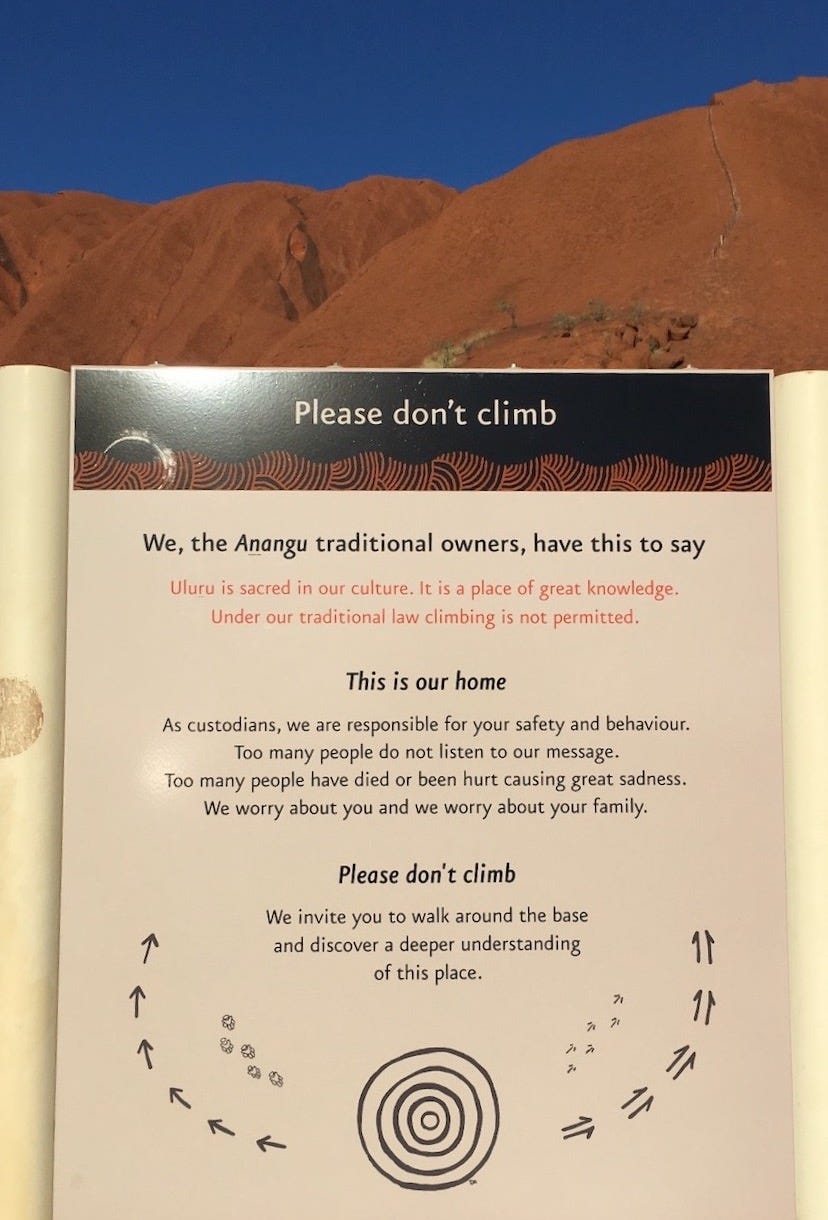

Another time, another sign, another location in Australia, I was taking a pilgrimage around Uluru, that extraordinary site of home, sacred power, connection, and magnificence. The request from the Anangu, the Indigenous Nation of that region, requested visitors not to climb Uluru, but at the time, there wasn’t a formal ban on climbing. The sign said:

I have remembered the appeal to the heart, the appeal to respect, the appeal to time and wider family circles, the appeal to both the past and the future at the core of such language. The Park Board have since ruled that Uluru cannot be climbed, a measure that was welcomed.

I've just arrived in Australia this weekend, and will be here for four weeks. I’ll see old friends and will do some poetry events, and I hope to see some of you Melbourne- and Sydney- and Brisbane-based folks while I'm here. So those two signs have been on my mind. I’ve wondered why. I think it’s because of the generosity in imagination of the communication: whether in delicious playful language, or earnest appealing language.

I’m curious what instances of generous language have stayed with you: language of signposts, of appeal, of invitation, of permission, or plea.

I look forward — every week — to reading what you say in the comments. It’s a lovely thing to be in this conversation about poetry and language and appeal and engagement.

Pádraig

Poetry in the World

Australia

Friends in the area, I’d be delighted to meet you.

May 2: Poetry reading at “Readings” in Carlton, Melbourne. 6:30pm. Free, but booking is essential.

May 5-7: Poetry and interviews at Sacred Edge Festival, Queenscliff, VIC. Tickets and information here.

May 11: Afternoon seminar on poetry, language and sacred text, and evening interview at St. John’s Cathedral, Brisbane.

Afternoon: 3pm-4:30pm (Tickets and info here).

Evening: 7pm-8:30pm (Tickets and info here).

May 12-13: Poetry Retreat in St. Kilda, Melbourne, in association with Small Giants Academy. Tickets and info here.

May 18: Poetry reading and interview in Sydney at Poetica Petit, with special music performance by Miriam Lieberman, plus an open mic session. 6pm-8pm. Tickets and information here.

USA

Returning and Becoming Conference | Asheville, NC

I’ll be sharing poetry and thoughts at a retreat at Kanuga (near Asheville, NC) on June 13 (morning and evening) and June 14 (morning). Hosted at an Episcopal Retreat Centre, this conference is open to all. My sessions will examine poetry, language, challenge, and change. Details and registration here.

Every weekday morning, my son and I turn onto Wonderwood Drive.

On our right side sits his school—a majestic lot, ancient oaks sagging with Spanish Moss, and plenty of places for the children to climb. Hand-painted signs bearing the school's golden rules line the perimeter: "Everyone Belongs," "Be Kind," and "Always Tell the Truth."

On our left side sits a strip club—an unkempt parking lot boasting blistered asphalt and a giant sign that reads "The Gentleman's Club: Where the Girls Are."

A tension buzzes in the space between these two worlds. A crossing guard (that looks an awful lot like Santa Claus) holds his stop sign, guiding backpacked siblings across the intersection.

I live in Saint Paul, Minnesota. In the summer of 2020, some of the more destructive incidents during the unrest that followed the murder of George Floyd occurred very close to my home. On a corner of the area’s busiest street, six blocks away, a small local business with an apartment above it was completely burned out. Directly across the street from it, another small business that also has an apartment on the upper floor was quickly boarded up, and spray painted on the plywood were the words, “People Live Here.”

It was a gut wrenching sight to drive by every day, this utterly helpless plea for forbearance, like the blood of a lamb on the doorposts, a desperate plea that the home would be spared from the chaos and destruction churning through the neighborhood.